Basics:

Sample program 1:

(* This is a comment. *)

(* variable binding and ints *)

val x = 34;

val y = 17;

val x = (x + y) + (y+2);

(* Conditionals *)

val abs_of_z = if z < 0 then 0 - z else z;

(* Calling a function *)

(* note that the parenthesis don't matter *)

val abs_of_z_simpler = abs z;

val abs_of_z_simpler2 = abs(z); Running in a REPL

To run an SML program in a REPL session, start the REPL with sml and type use "name_of_file.sml";

In short, when calling a file:

- Program is type checked and types are stored in static environment

- If no errors are found, a program is evaluated with expressions stored in a dynamic environment.

use

use "file.sml" is an unusual expression. Think of it as taking the contents of the file and typing each of the bindings in the file one at a time in the REPL.

The REPL

Stands for Read-Eval-Print-Loop. SML reads the program and type checks, evaluates the expressions, prints the results of the evaluation (or any error) and then loops for another prompt.

We can treat it as a convinient way to run programs or to try a few things. However, sometimes it may be worth to write tests in a secondary, test file and then calling both.

Note: never call use on the same file twice.

Errors

- Syntax: What you wrote means nothing or the construct you wanted

- Type checking: What you wrote doesn’t type check

- Evaluation: It runs but produces a wrong answer, an exception, or an infinite loop

When debugging we must check all three possibilities; the error messages in ML will not be very specific. Additionally, type error messages in SML are quite bad.

Comments

(* Comments are started with "star + open bracket" and end with the opposite)Variable bindings

Variables as created with the following syntax:

val x = e;Syntax:

- Keyword

valand punctuation=and; - variable

x - Expression

e(which can contain subexpressions)

val is a keyword for a variable. = is the assignment operator, and afterwards we set 34 as the expression.

When running this in a REPL, we will then see the following:

- use "first.sml";

[opening first.sml]

val x = 34 : int

val y = 17 : int

val it = () : unitThe last line is telling us the output of calling first.sml.

When using bindings, we can use established bindings as part of an expression; however, we cannot use later bindings in earlier expressions. This is because the program works in the following way:

(* static environment: x : int *)

(* static environment: y : int *)

(* static environment: z : int *)

val x = 34;

(* dynamic environment: x --> 34 *)

val y = 17;

(* dynamic environment: x --> 34, y --> 17 *)

val x = (x + y) + (y+2);

(* dynamic environment: x --> 34, y--> 17, z --> 70 *)

When we have addition expressions with variables, SML looks up the value in the dynamic environment and then follows the order of operations.

Note that before any of these events ocur, the file is first “type checked”, as ML is a languge with a type system. What this means is that it makes consistent assumptions about what various types are (for example, what an int is.) This is accomplished initially with a static environment.

More specifically, the program completes a first pass of the file and creates a static environment to establish the types of each variable. IT then enters the REPL session as we know it.

Note, too, that for z the static environment established it as an int. This is because as the type checker does its work, it notices that there is an addition operation composed of variables with type int in either side.

Conditionals

val abs_of_z = if z < 0 then 0 - z else z;

(* static environment: ..., abs_of_z : int *)

(* dynamic environment: ... , abs_of_z --> 70 *)A conditional is evaluated by first looking at the first expression, if z < 0. It then looks up the value of z in the dynamic environment, and asks less than?. If false, it ignores the then and simply evaluates the else.

The if expression can be summarized as follows:

val abs_of_z = if (* bool *) then (* any *) else (* any *);

(* dynamic environment: .... abs_of_z --> (* any *) *)Expressions

Every expression has:

- Syntax

- Type checking rules:

- Produces a type or fails

- Evaluation rules (only used on things that type check)

- Produces a value, exception, or infinite loop

Thus when writing an expression, ask:

- What is the required syntax? How do you write it down?

- What are the types of the expression, and what can cause the type check to fail?

- What are the evaluation rules? If it does type check, how does it perform its computation to produce a value?

Variables

- Syntax:

- Any sequence of letters, ditigs, or

_ - Cannot start with a digit

- Any sequence of letters, ditigs, or

- Type-checking:

- Appies when using a variable, not when defining the variable.

- Look up type in current static environment; if not found, fail.

- Evaluation:

- Look up value in current dynamic environment.

Addition

- Syntax:

- Any expression that has at least 2 subexpressions with

+between them e1 + e2wheree1ande2are expressions

- Any expression that has at least 2 subexpressions with

- Type checking:

- If

e1ande2have typeint, thene1 + e2has typeint - Else, type check fails.

- If

- Evaluation:

- If

e1evaluates tov1ande2evaluates tov2, thene1 + e2evaluates to sum ofv1andv2.

- If

Values

- All values are expressions.

- Not all expressions are values.

- Every value “evaluates itself” in “zero steps”

- That is, 42 always evaluates to 42; true evaluates to true.

Conditionals

- Syntax

- if

e1thene2elsee3 - where

if,thenandelseare keywords ande1 e2 e3are subexpressions.

- if

- Type checking

e1must have type boole2ande3can have any typet, but they both must be of same typet- the type of the entire expression is

t

- Evaluation

- evaluate

e1to a valuev1 - if

v1is true, evaluatee2and the result is the result of the whole expression - else, evaluate

e3and the result is the result of the whole expression

- evaluate

Comparisons

x < y

- Syntax

e1 < e2

- Type checking

e1ande2must be of typeint- the type of the expression is of type

bool

- Evaluation

- evaluate

e1ande2tov1andv2 - if

v1<v2, the whole expression istrue

- evaluate

Shadowing

Shadowing is the process of adding a variable to an environment where the variable already existed in that environment.

val a = 10

(* a:int, a -> 10 *)

val b = a * 2

(* b -> 20 *)

val a = 5

(* a -> 5, b -> 20 *)

val c = d

(* a -> 5, b -> 20, c -> 20 *)Here c is asigned to the result of the expression of b; as a result, for the definition of c b then becomes irrelevant.

Note, too, that val a =5 is not an assignment statements. There is no wat to mutate a value, instead a is now a different value in a different environment.

In other words, after every expression a new dynamic environment is created. When shadowing, a REPL session will tell us that an older value was hidden value.

val a = 1

val b = a (* b is bound to 1 *)

val a = 2- Expressions in variable bindings are evaluated “eagerly”:

- Before the variable binding “finishes”

- After, the expression producing the value is irrelevant

- There is no way to “assign to” a variable in ML:

- Variables can only be shadowed in later environments.

In other words, the way in which b was bound to 1 is irrelevant. Once the binding is complete, previous computation does not matter, since in the current environment b -> 1.

Functions

In ML, functions work much like Java methods: they have arguments and a result. However, they do not have classes, such as this, return, etc.

Example function binding:

val x = 7

(* Note: correct only if y>=0 *)

fun pow (x : int, y : int ) =

if y=0

then 1

else x * pow(x,y-1)

fun cube(x : int) =

pow(x,3)

val sixtyfour = cube 4

(* val sixtyfour = cube(4) is also legal *)In REPL sessions, functions are represented by fn. We are also told the type that is passed into the function with a *-separated list of types, and finally the type of the functions result, noted by ->.

Common gotchas

- Bad errors messages if you mess up function argument syntax.

- The use of

*in type syntax is not multiplication. - Cannot refer to later function bindings.

Function bindings

-

Syntax

fun x0 (x1 : t1,... xn :tn ) = e

-

Evaluation:

- A function is a value!. When we have a function binding, x0 is added to the dynamic environment so that later expressions can call it.

-

Type checking:

-

Adds binding x0 : (t1 * … * tn) → t if:

-

Can type-check body

eto have typetin the static environment containing:- “Enclosing” static environment (earlier bindings)

x1 : t1, ..., xn : tn(arguments with their types)x0 : (t1 * ... * ..tn) -> t(for recursion)

-

The overall type-checking result is to give

x0typetin rest of program, not for earlier bindings -

Arguments can only be used in

eand only exist in the static environment fore. -

The return type of

x0,t, is the type ofe.

-

Function Calls

-

Syntax

e0 (e1, ..., en)- Note that parenthesis are option if there is exactly one argument

-

Type-checking:

- if

e0has some type(t1 * ... * tn) -> te1has typet1, …enhas typetn

- then

e0(e1,...,en)has typet

- if

-

Evaluation

- (Under current dynamic environment) evaluate

e0to a functionfun x0 (x1 : t1, ..., xn : tn) = e - (Under current dynamic environment) evaluate arguments to values

v1,...,vn - Result is evaluation of

ein an environment extended to mapx1tov1…xntovn

- (Under current dynamic environment) evaluate

For example, pow(2, 2+2) is will be evaluated by first looking up pow to get a function binding. Then, the first argument 2 is already evaluated, and we move on to 2+2, which itself will be eagerly evaluated (meaning the function itself will only ever see the result of 2+2, not the expression itself). Finally, the function body is evaluated by extending the dynamic environment where the function was created with extra values for the arguments of the function.

Pairs and other Tuples

Pairs

Build

- Syntax:

(e1,e2) - Evaluation:

- Evaluate

e1tov1ande2tov2. Result is(v1,v2). - Note that a pair of values is a value

- Evaluate

- Type checking:

- if

e1 : taande2 : tb, then the new pair expression(v1,v2) : ta * tb

- if

Access

- Syntax:

#1 eand#2 e - Evaluation: evaluate

eto a pair of values and return first or second piece- Example: if

eis a variablex, then look upxin environment

- Example: if

- Type checking:

- If

ehas typeta * tb, then#1 ehas typetaand#2 ehas typetb

- If

Tuples

A pair is simply a 2-Tuple. To generalize we can say for tuples:

(e1, e2, ..., en)ta * tb * ... * tn#1 e, #2 e, ..., #n e

Note that tuples and other types can be nested.

Additionally, tuples are really just syntactic sugar for records. For example, consider the following:

- val a_pair = (3+1, 4+2);

val a_pair = (4,6) : int * int

- val a_recors = {second=4+2, first=3+1};

val a_recors = {first=4,second=6} : {first:int, second:int}

- val another_pair = {2=5, 1=6};

val another_pair = (6,5) : int * int

- val x = {3="hi", 1=true};

val x = {1=true,3="hi"} : {1:bool, 3:string}

- val y = {1=true, 3="hi", 2=3+2};

val y = (true,5,"hi") : bool * int * string

- val z = {2=1, 3=1};

val z = {2=1,3=1} : {2:int, 3:int}Remember that the access method for either tuples or records is with the #<field name> notation, where tuples are position based and records are field based. Furthermore, records will be organised alphanumerically, and thus if the field names of the records are ascending numerical values starting at 1, then a record is exactly like a tuple.

In other words, tuples don’t exist. They are syntactic sugar for records with fields named 1,2…n.

Lists

Unlike tuples, which are immutable, lists can be expanded or shortened. However, every item in a list must be of the same type.

Build

- Empty list is a value:

[] - In general, a list of value is a value; elements separated by commas:

[e1, e2, e3] - We can also building lists with the

consoperator, written with a double colon::.- If

e1evaluates tovande2evaluates to a list[v1, ..., vn], thene1::e2evaluates to[v, v1, ..., vn]. - This is much like Racket

(cons e1 e2)→(list e1 e2). - We can chain the cons, too:

6::3::8::x(like in Racket,(cons 6 (cons 3 (cons 8 (cons x empty))))) - Note that we cannot do

[6]::[1,2,3], since we cannot add an item of typeint listinside a list of ints.

- If

Access

null eevaluates totrueif, and only if,eevaluates to[].

var x = [1,2,3]

null x -> false

null [] -> true- If

eevaluates to[v1,v2,...,vn]thenhd eevaluates tov1, whiletl eevaluates to the rest of the list.- Comparing it to racket, this a self-reference list where

hd eequates to(first los)andtl eequates to(rest los). Notice that there isn’t a requirement to includeempty, although the tail of a single element list is still the empty list.

- Comparing it to racket, this a self-reference list where

Type-checking list operations

For any type t, the type t list describes lists where all elements have type t. In other words, a list can have a type t of any type, where that type can be int list, bool list, int list list, (int * int) list etc, so long as all elements of that list are the same type (in short, we can nest the types, so long the overall list structure has elements which are all of the same compound type)

The empty list, [], can have type t list of any type (it can be an int, bool, or even (int * bool * int)) which is indicated in SML by 'a list (known as “quote a” or “alpha”). Because of this property, we can always cons any item of type t onto the empty list.

When we are using cons to build a list, we need e1::e2 to type-check successfully. This is accomplished where we have a type t such that e1 has type t and e2 has type t list. This results in a list of type t list.

??? Can we cons e1 of type t list onto e2 of type t list?

List functions

Functions over lists are usually recursive; this is the only way to get to all the elements. Some questions one should ask is “what is the base case? what is the non-base case?“. Similarly, functions that produce lists of arbitrary size will be recursive - often in the form of a list made out of smaller lists.

Functions over lists

fun sum_list (xs : int list) =

if null xs

then 0

else (hd xs) + sum_list(tl xs)

fun list_product (xs : int list) =

if null xs

then 1

else hd xs * list_product(tl xs)

(* int -> int list *)

(* consumes a number n and produces list [n, n-1,... n-n] *)

fun countdown (x : int) =

if x=0

then []

else x :: countdown(x-1)

fun append (xs : int list, ys : int list) =

if null xs

then ys

else (hd xs) :: append ((tl xs), ys)

Functions over pairs

These functions operate on parameters of type (int * int) list.

fun sum_pair_list (xs : (int * int) list) =

if null xs

then 0

else #1 (hd xs) + #2 (hd xs) + sum_pair_list(tl xs)

(* consumes a list of pairs and returns a list with the first element of each pair *)

fun firsts (xs : (int * int) list) =

if null xs then []

else #1 (hd xs) :: (firsts (tl xs))Let Expressions

Let expressions allow us to introduce local expressions so we can have better style and efficiency.

- Syntax

let b1 b2 ... bn in e end- Each

biis any binding andeis any expression.

- Each

- Type checking

- Type check each binding in order in a static environment that includes previous bindings. Type of whole let-expression is the type of

e.

- Type check each binding in order in a static environment that includes previous bindings. Type of whole let-expression is the type of

- Evaluation

- Evaluate each

biandein order in a dynamic environment that includes the previous bindings. The result of the whole let-expression is the result of evaluatinge. - The bindings have no effect on any environment except inside the

letexpression.

- Evaluate each

fun silly2 () =

let

val x = 1

in

(let val x = 2 in x+1 end) + (let val y = x+2 in y+1 end)

endWhen evaluating the above code, we have a dynamic environment were x = 1. Once we enter the first let expression, x=2 will shadow our original environment and the result of let val x = 2 in x+1 end will be 3. When we move on to the second let expression, the x is then pulled from the function’s environment, and so y evaluates to 4.

Substitution looks like this:

let val y = 1 + 2 in y + 1let val y = 3 in y + 1let val y = 3 + 1let val y = 4

Nested Functions

(* nested functions *)

fun countup_from1 (x : int) =

let

fun count (from : int, to : int) =

if from=to

then []

else from :: count(from+1, to)

in

count(1,x)

endWhen comparing this to Racket and HTDF recipes, we can see that the let expressions roughly correspond to (local [(define .... expressions. The in, then, is equivalent to the trampoline when using local functions.

Options

t option is a type for any type t, much like t list.

Building:

NONEhas type'a optionSOME ehas typet optionifehas typet

Access:

isSomehas type'a option' -> boolthat returnstruefor the non-empty case (trueifSOME,falseifNONE)valOfhas type'a option -> 'a(exception given ifNONE).

(* fn : int list -> int option *)

fun max1 (xs : int list) =

if null xs then NONE

else

let val tl_ans = max1(tl xs)

in if isSome tl_ans andalso valof tl_ans > hd xs

then tl_ans

else SOME (hd xs)

endHere the return value of max1 is of type int option. Thus, we need to check first whether the value in the recursive call isSome (that is, whether it is NONE or not). If not NONE, we also have to compare the valOf (that is, the value 'a of something with type 'a option) with the head of our list.

This also means that trying to operate on the return of max1 needs to be augmented by using valOf:

(max1 [3,7,5]) + 1 (* will fail type check, adding 'a option to int*)

((valOf (max1 [3,7,5]))) + 1 -> 8 intfun max2 (xs : int list) =

if null xs then NONE

else let

fun max_nonempty (xs : int list) =

if null (tl xs) (* inner xs will always be nonempty, given local

scope *)

then hd xs

else let val tl_ans = max_nonempty(tl xs)

in

if hd xs > tl_ans

then hd xs

else tl_ans

end

in

SOME (max_nonempty xs)

endBooleans

- *

e1 andalso e2- Type checking:

e1ande2must have typebool

- Evaluation:

- If

e1isfalsethenfalse, else the result ofe2

- If

- Type checking:

e1 orelse e2- Evaluation: if

e1istrue, then true, else result ofe2

- Evaluation: if

Booleans without boolean operations

(* e1 andalso e2 *)

if e1

then e2

else false

(* e1 orelse e2 *)

if e2

then true

else e2

(* not e1 *)

if e1

then false

else trueComparisons

For comparing int values: = <> > < >= <=

Note that > < >= <= can be used with real, but not between int and real (a solution is to call Real.fromInt arg to convert an int to a real); = <> can be used with any “equality type” but not with real because floating point numbers, due to rounding errors, cannot be ascertained to be truly equal.

(remember that a real is a floating point number in ML)

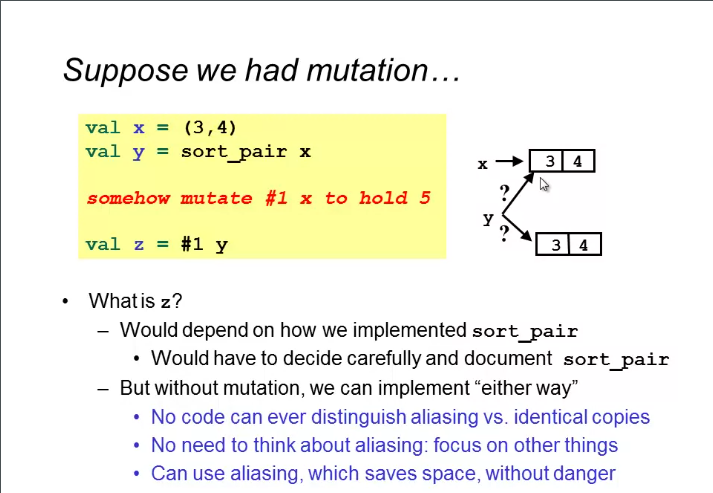

Benefits of No Mutation

One of the major aspects of functional programming is that we cannot mutate a piece of data once it has been created; instead, we must create new data. This is because we cannot mutate or change existing data - this is a feature, since the inability to change it means code can be executed more predictably.

Consider the following functions:

fun sort_pair (pr : int * int) =

if #1 pr < #2 pr

then pr

else (#2 pr, #1 pr)

fun sort_pair (pr : int * int) =

if #1 pr < #2 pr

then (#1 pr, #2 pr)

else (#2 pr, #1 pr)In a functional language with not mutability, such as SML, the effects of both functions is exactly the same. An existing codebase that changes from the later to the former or vice-versa will not see any difference. In other words, both implementations are indistinguishable because tuples are immutable. In a language that has mutable compound data, these would be considered completely different functions.

The advantage here is that given the existence of mutation we can get into an issue with creating an alias. For example:

val x = (3,4)

val y = sort_pair x

*somehow mutate #1 x to hold 5*

val z = #1 yThe question here is whether y itself points to a separate value of (3,4) or to the same (3,4) that x points to. The latter is an alias, and in a language with mutable data, mutating the value of x means there is ambiguity about the value of y.

Of note, in ML values will be aliased. However, it is impossible to tell whether they are or not, and there is no danger of breaking code because of it.

Records

Records a particular “each of” type. They are used with { } syntax:

val x1 = {first=(1+2, true andalso true), second=3+4, third=(false, 9)}

val x1 = {first=(3,true),second=7,third=(false,9)} :

{first:int * bool, second:int, third:bool * int}

Here each of the values in the record will be evaluated. Note, too, that the order in which they are placed is immaterial (although SML will print them alphabetized.) We are able to nest them, pass them into functions, etc.

To access the values in a record, we use the syntax #<field name> record. For example:

#first x1;

val it = (3,true) : int * boolNote that we don’t have to assign the record to a value:

#h {f=3, h=2, p=5}Rules

Record values have fields holding values:

{f1 = v1, ..., fn = vn}Record types have fields holding types:

{f1 : t1, ..., fn : tn}Note that records are very much like tuples. The main difference is that tuples are slightly shorter, but records allow us to access values by name instead of position.

Quirks

Negative values of a single argument must be written either as an expression, such as val a = 0 - 5 or with the negation operator, ~: val a = ~5.

Division between reals (same as floats) can be accomplished with /, such as val v = 1.0 / 0.5. However, for int we must use div: val v = 1 div 2

Datatypes

Custom data structures are created with datatype bindings.

Building datatypes

The structure to create these datatype bindings is as follows:

(* the mytype datatype is a one of for each option separated by a pipe *)

datatype mytype = TwoInts of int * int

| Str of string

| PizzaBy creating this binding, we are adding constructors to our environment (both static and dynamic) - in this case, the constructors are TwoInts, Str, and Pizza - as well as the new type name. What the constructors do is they are functions where, given inputs of the correct types, return something of mytype.

Any value of type mytype is made from one of the constructors. Its value will have two parts: the “tag” which tells you the constructor used to make the value, and the corresponding data.

As a result, TwoInts is in the environment and is a function of type int * int -> mytype. Note that Pizza is already a value if type mytype.

Note that when creating the datatype bindings, the values of a specific data type will be <constructor> <value>, not just the value itself. They are telling us what type of mytype the underlying value is - one can think of them as tags that tell us what type they are. For example:

(* using datatype mytype *)

val a_datatype = Str "hi"

val b_datatype = Str

val c_datatype = Pizza

val d_datatype = TwoInts(1+2,3+4)

val e_datatype = a_datatype

(* REPL output*)

val a_datatype = Str "hi" : mytype

val b_datatype = fn : string -> mytype

val c_datatype = Pizza : mytype

val d_datatype = TwoInts (3,7) : mytype

val e_datatype = Str "hi" : mytypeUsing datatypes

For one of types, there are two aspects to accessing a value:

- We need to check what variant it is - find out which constructor made it.

- Extract the data itself, if the variant has any.

Note that other one-of types do similar things:

nullandisSomeboth are checking the “tag” associated with a particular valuehd,tl, andvalOfare used to extract data from a particular construct.

Case Expressions

This is the construct used to access values in datatype bindings.

fun f x =

case x of

Pizza => 3

| Str s => 8

| TwoInts(i1, i2) => i1 + i2 With this function, we pass an argument to type mytype and we use the case expression to branch into the different possibilites of the one-of. For example, given a Pizza, the function will return 3. Given a TwoInt(y,z), this function will move to the third branch, place y and z in the local environment of that branch, and produce the result of y+z.

Remember, however, that all function returns must be of the same type.

The way the case works is that x is evaluated, and then we check which pattern matches. The function will go into the branch that first fits the matche pattern. Note that the scope of any variable in a branch is only inside that branch.

Pattern matching

the general syntax for pattern matching is:

case e0 of

p1 => e1

| p2 => e2

...

| pn => enEach pattern is a constructor name followed by the right number of variables. They look like expressions, but they are not expressions, and thus they are not evaluated - we only check if something matches.

The pattern matching, at its simplest form, consists of checking whether we have a constructor C on its own, or C x (meaning constructor and a value), or C (x,y) (meaning constructor and a 2-tuple), etc…

The case for pattern matching

- You can use pattern-matching to write your own testing and data-extractions functions if you must.

- You cannot forget a case (inexhaustive pattern-match warning)

- For example, given two branches that follow the same pattern, we will have a redundant error raised; alternatively, if we forget a case we will have a warning “match nonexhaustive” or a runtime exception telling us we missed a pattern.

- You cannot duplicate a case

- You will not forget to test the variant correctly and get an exception

- Pattern-matching can be generalised and made more powerful, leading to elegant and concise code.

Useful datatype examples

Note that all of these enums are either one type or the other

- Enumerations, including carrying other data:

datatype suit = Club | Diamond | Heart | Spade

datatype rank = Jack | Queen | King | Ace | Num of intWe could then combine this with an “each of” datatype to have cards with suit and rank.

- Identities

datatype id = StudentNum of int

| Name of string

* (string option)

* stringCompare the above datatypes with one-of types with the bad style of forcing each-of types onto a problem:

(* use the student_num and ignore other fields unless the student_num is ~1 *)

{ student_num : int,

first : string,

middle : string option,

last : string}The disadvantage here is that it is more verbose, gives up the benefit on enforcing every value in one variant, and lets you forget about branches. for example, in this example we may prefer to use a sutdent_num unless a specific value is present to force us into using the rest of the construct.

A better scenario to use an each-of type, in which we have an object that has both student names and student numbers. In that scenario, use the following:

{ student_num : int option,

first : string,

middle : string option,

last : string}Expression trees

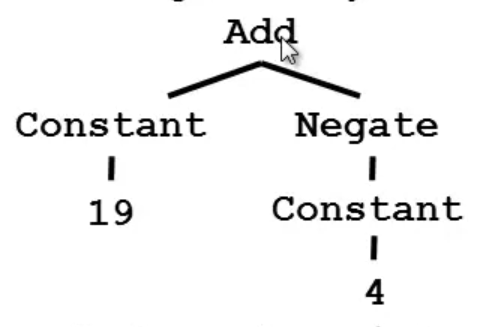

Using self-reference we can create a language of arithmetic expressions:

datatype exp = Constant of int

| Negate of exp

| Add of exp * exp

| Multiply of exp * expThis is a self-reference because some of these branches refer to themselves. It is, in fact, a definition for a tree with a constant number attached.

this would allow us to do something like this:

Add (Constant (10+9), Negate (Constant 4))A pictorial representation of the above would be this:

With this representation, we can create functions that perform arithmetic over a datatype exp (note that functions over recursive datatypes are usually recursive):

fun eval e =

case e of

Constant i => i

| Negate e2 => ~ (eval e2)

| Add (e1, e2) => (eval e1) + (eval e2)

| Multiply (e1, e2) => (eval e1) * (eval e2)Note how on the right-side of the function we are using a recursive structure to pass the values into eval again.

Definitions

Datatypes

datatype t = C1 of t1 | C2 of t2 | ... | Cn of tnAdds type t and constructors Ci of type ti -> t, where Ci v is a value and the result includes the tag. If we have a constructor that is just a tag, we can skip the of t to say we have no underlying data.

to access the data, we use an expression where given type t, use case expressions to see which variant it has and extract underlying data.

Case expressions

case e of p1 => e1 | p2 => e2 | ... | pn => enA case expression can be used anywhere an expression goes; it doesn’t need to be the whole function body, but often is.

Evaluation rules

- Evaluate

eto a valuev - If

piis the first pattern to matchv, then result is evaluation ofeiin environment “extended by the match”- Note that the pattern matching follows the order written in the program, even through the datatype is represented alphabetically.

- Pattern

Ci (x1,...,xn)matches valueCi(v1,...,vn)and extends the environment withx1tov1…xntovn

Example

datatype exp = Constant of int

| Negate of exp

| Add of exp * exp

| Multiply of exp * exp

fun max_constant e =

let fun max_of_two(e1,e2) =

let

val m1 = max_constant e1

val m2 = max_constant e2

in

if m1 > m2 then m1 else m2

end

in

case e of

Constant i => i

| Negate e2 => max_constant e2

| Add (e1, e2) => max_of_two(e1,e2)

| Multiply (e1, e2) => max_of_two(e1, e2)

end

val test_exp = Add (Constant 19, Negate (Constant 4))

val nineteen = max_constant test_expNote that the above can be re-written using the built-in function Int.max:

datatype exp = Constant of int

| Negate of exp

| Add of exp * exp

| Multiply of exp * exp

fun max_constant e =

(* ??? *)

let fun max_of_two(e1,e2) =

Int.max(max_constant e1, max_constant e2)

in

case e of

Constant i => i

| Negate e2 => max_constant e2

| Add (e1, e2) => max_of_two(e1,e2)

| Multiply (e1, e2) => max_of_two(e1, e2)

end

val test_exp = Add (Constant 19, Negate (Constant 4))

val nineteen = max_constant test_expBecause when passing arguments to functions the arguments are evaluated before the function fires, calling Int.max(max_constant e1, max_constant e2) is efficient and does not grow exponentially.

Consider that the use of built-ins allows us to remove the local function to simplify further:

fun max_constant e =

case e of

Constant i => i

| Negate e2 => max_constant e2

| Add(e1,e2) => Int.max(max_constant e1, max_constant e2)

| Multiply(e1,e2) => Int.max(max_constant e1, max_constant e2)Type synonyms

A datatype binding introduce a new type name, and the only way to create values of this new type is with it’s type constructor.

A type synonym is created with the syntax:

type aname = twhere type is a keyword, aname is an arbitrary name, and t is an existing type. This allows us to use both aname and t entirely interchangeably.

datatype suit = Club | Diamond | Heart | Spade

datatype rank = Jack | Queen | King | Ace | Num of int

type card = suit * rank

type name_recors = {student_num : int option,

first : string,

middle : string option,

last : string }

fun is_Queen_Of_Spades (c : card) =

#1 c = Spade andalso #2 c = Queen

val c1 : card = (Diamond, Ace)

val c2 : suit * rank = (Heart, Ace)

val c3 = (Spade, Ace)

(* We can call is_Queen_Of_Spades with any of c1, c2, c3 *)The result of running the above program is as follows:

datatype suit = Club | Diamond | Heart | Spade

datatype rank = Ace | Jack | King | Num of int | Queen

type card = suit * rank

type name_recors =

{first:string, last:string, middle:string option, student_num:int option}

val is_Queen_Of_Spades = fn : card -> bool

val c1 = (Diamond,Ace) : card

val c2 = (Heart,Ace) : suit * rank

val c3 = (Spade,Ace) : suit * rank