camelCase.py

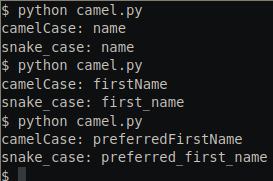

Week 2 of CS50 Python’s problem sets starts with a program called camelCase, wherein the program will ask the user for a name (in camel case) and output the corresponding name in snake_case.

Here is an example:

First I will show my complete solution, then I will discuss the code and my decisions.

def main():

"""

program that prompts the user for the name of a variable in

camel case and outputs the corresponding name in snake case.

Assume that the users input will indeed be in camel case.

"""

string = input("cameCase: ")

convert_to_snake_case(string)

def convert_to_snake_case(string: str) -> str:

"""

Takes a string as input and outputs a string where

every upper-case char is prefixed with "_" and converted

to lower case.

"""

snake = ""

for i in string:

if i.isupper():

snake += "_" + i.lower()

else:

snake += i

print("snake_case: " + snake.lstrip("_"))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()The main() function begins by asking the user for input and storing the value in a variable called string, which is then passed on to the convert_to_snake_case function as an argument.

The second function begins by initializing an empty string named snake. Then:

- For each character in the string, ask whether it is uppercase or not via

.isupper(). - If it is uppercase, add an underscore,

_and the character in lowercase to thesnakestring. - If it is not upper case (in other words, it is lower case, a digit, or a special symbol), simply add it to the

snakestring. - Once the loop is complete, take care of the edge case where the first character of the input string was upper case. In this scenario, simply stripping any underscore from the left side of the string should do it.

The two “Pythonic” things I’ve done here are to use the += operator to add each character to the string, and to use the string concatenation operator in the print statement.

Note that this solution goes beyond the requirements of the CS50 problem set. It does not assume that the input is already in camelCase - rather, it more generally converts strings with uppercase characters into snake_case.

coke.py

The next problem of the week requires us to write code for a machine that sells bottles of coke for 50 cents each. The issue is that the machine only accepts coins in 25 cent, 10 cent, and 5 cent denominations. Our task is to create a program that asks the user to insert a coin, one at a time, until the balance due is paid. At the end, the program must inform the user how much change is owed, whether 0 or more.

While I could probably write the code directly without functions - or at least without a need for a main function and other nested ones - I am getting in the habit of using main() as a starting point. From there I am taking the approach of How To Design Programs by writing small pieces of code and creating wish-lists as I go. Note that I am declaring a constant above main() to indicate the cost of each bottle, as I expect to re-use that value elsewhere:

COKE = 50

def main():

insert_coin()

def insert_coin(coin):

!!!

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()I am assuming that I will start with a function that takes a coin. Rather than write it all out, I simply call the function and begin a definition for that function. The use of !!! in the definition is there so that I can ctrl-f for it (as I get into larger programs) to find parts yet unfinished.

The pseudo-code for this program is as follows:

- Print amount due

- Ask for coin

- Check that coin is in valid denomination

- Check if payment is sufficient

- Subtract coin from amount due

- Loop until coins >= COKE

- Subtract COKE from coins and print change owed

Given that point #5 in the pseudocode asks for a loop, and that loop includes the requirement to print the current amount due, I figure I should solve this with the use of recursive calls to the same function from the get-go. The concept is simple: create an infinite loop whose only break condition is a situation where total coins inserted exceed the value of the item being sold.

COKE = 50

DENOMINATIONS = [25, 10, 5]

def main():

# The world starts with 50 due and 0 given

insert_coin(COKE, 0)

def insert_coin(due, given):

# Print Amount Due

print("Amount due: ", COKE - given)

# Ask for coin

coin = int(input("Insert coin: "))

if coin not in DENOMINATIONS:

insert_coin(due, given, coke)

# Check if payment is sufficient

if coin + given < COKE:

# Subtract coin from amount due and ask for money again

insert_coin(due, given + coin)

else:

# Print amount owed

print("Change owed:", abs(COKE - coin - given))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()This is the entire code. The definition of insert_coin takes two arguments: how much money is due, and how much has been given so far. The purpose of this is two-fold: 1) it allows this function to be initialized with COKE (which holds a value of 50, and can easily be changed by changing the constant at the top of the file) and 0, since the user has not given any money yet, and 2) the same paradigm can be used in a recursive call.

After printing how much is due (via simple subtraction of COKE minus the total given so far), the function asks for input. If the input is not in a valid denomination, call the same function again with the same values. This simply loops back to the point where input is requested, with no changes whatsoever.

Should the input match a valid denomination the first if statement won’t run, and we move into checking whether the current input plus all inputs before are sufficient. If they are not, call the same function again, but update how much money has been deposited.

On the other hand, if sufficient payment has been delivered we move into the else statement, which simply prints how much change is owed by subtracting the total coin inputs (included the current one) from the value of a bottle of coke. Because this number should be ⇐ 0, I included the abs call to make sure we print the absolute value.

I probably could have simplified this program by not including the extra function. In fact, I could probably use a single while loop rather than recursive function calls. I will say, my solution does allow for scaling up accepted denominations and to easily change the value of the item being sold without having to dig into the code.

In theory it could also do discounts by simply subtracting from the value of COKE, I guess.

twttr.py

In twttr.py we are tasked with setting up a program that takes user input and prints it after removing all vowels.

My implementation of the problem is fairly simply. I begin by declaring a constant, VWLS (get it?) that contains a list of all vowels in lowercase.

From there, I take input from the user and save it to the s variable. I initialize an empty string (which will be used to concatenate the result) and then I iterate through the input string in a for loop.

The only “fancy” stuff I’ve done here is abstract away the question in the if statement. Rather than include an ugly block of if...then... it feels much more readable to simply ask “is this a vowel?“. If it is a vowel, the loop continues without doing anything - that is, it does not add the character to the o string variable. If it is not a vowel, it can be added to o.

After that, simply print the output.

VWLS = ["a", "e", "i", "o", "u"]

def main():

"""

prompts the user for a str of text and then outputs

that same text but with all vowels (A, E, I, O, and U)

omitted, whether inputted in uppercase or lowercase.

"""

s = input("Input: ")

o = ""

for i in s:

if is_vowel(i):

continue

else:

o += i

print("Output:", o)

def is_vowel(s):

return True if s in VWLS or s.lower() in VWLS else False

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()plates.py

In plates.py we are tasked with writing a program that validates vanity license plates based on the following requirements:

- All plates must start with at least two letters

- They may contain a maximum of 6 characters (letters or numbers) and a minimum of 2 characters

- Numbers cannot be used in the middle of a plate; they must be used at the end. For example, AAA222 would be valid; AAA22A would not.

- The first number cannot be a 0.

- No periods, spaces, or punctuation marks are allowed.

We are also given the following starting code:

def main():

plate = input("Plate: ")

if is_valid(plate):

print("Valid")

else:

print("Invalid")

def is_valid(s):

...

main()Looking at a list of requirements like that suggests to me that each requirement will have, at least, one function. And so, I begin by writing a wish-list of functions in is_valid:

def is_valid(s):

character_limits(s)

are_numbers_at_end(s)

valid_zeros(s)

no_punctuation(s)You may note that I said each requirement would have it’s own function, and yet I have 4 functions for 5 requirements. That’s because I’m writing this post-fact, and I found that the first two requirements sort of made sense within the same function.

def character_limits(s):

"""

Checks if input lenght is between 2 and 6 chars inclusive.

If so, returns True iff the first two characters are letters.

"""

l = len(s)

if l > 1 and l < 7:

return s[:2].isalpha()

return FalseThe first step in this function is to save the length of the input string into a variable l. For small programs like this this is probably a useless optimization, but something something about habits I guess… In any case, we save the variable so that on the next line of code we can check whether the length is more than 1 (meaning at least 2) and less than 7 (meaning at most 6). Rather than calculating the length twice, we only had to do it once by having the variable stored in l.

Assuming that the length of the string is appropriate, the next line simply returns a boolean value. The isalpha() string method returns True if all characters in the string are alphabetic (and there is at least one character). We can then use list slices - that’s the [:2] syntax there - to indicate that we only want from the beginning up to the second character of the string. Thus, s[:2].isalpha() will evaluate to True only if the first two characters are alphabetical, False otherwise.

def are_numbers_at_end(s):

"""

Numbers cannot be used in the middle of a plate;

they must come at the end.

For example, AAA222 would be an acceptable vanity plate;

AAA22A would not be acceptable.

"""

# Check if there are numbers in string

for i in range(len(s)):

if s[i].isdigit():

# Check that the numbers are at the end

return s[i:].isdigit()

return True

This function is what took me the most to figure out. The goal is not only to check if there are numbers in the string, but to make sure that all numbers occur after the alphabetical characters.

Here I make use of .isalpha()’s counterpart, isdigit(). As one may expect, this method returns True if all characters in a string are digits. And so, the first step is to check whether there are any digits in the first place - consider, for instance, that a plate with ABCDEF would still be valid. I use a for loop to iterate over the length of the string; note though that this is different from iterating over the string itself. By iterating over its length, i is a series of numerical values - an index for the string. This becomes relevant because we care about where exactly the digits are relative to other characters.

If the for loop completes and no numbers are found - meaning the .isdigit() conditional never evaluates to True, the function simply returns True. There are no digits and so we don’t need to bother checking whether they are at the end or not.

On the first instance of finding a digit, however, we must then ask whether the rest of the string is composed of digits. And so the function simply returns the expression s[i:].isdigit(). Remember that isdigit() returns True if all characters in the string are digits; and so, from the index i of the first digit we can see if the rest [i:] of the string has digits. And because this is a boolean expression we can simply use it in the return statement.

def valid_zeroes(s):

"""

The first number used cannot be a 0.

"""

# Check if any zeroes in string

if "0" not in s:

return True

for i in range(len(s)):

if s[i].isdigit():

# Extra brackets added for clarity

return not (s[i] == "0" and s[i:].isdigit()) valid_zeroes is similar to are_numbers_at_end. I do begin with a shortcut though: if there are no zeroes in the string, we can skip the whole thing.

Assuming a zero is present in the string, however, we follow the same logic as before: index the string and ask whether each index position is a digit. If it is a digit, then return a boolean.

The question in the return statement is “if this current number is a zero, are there numbers after it?” Consider the case where the plate we want is CS50:

- There is a zero in the string, so skip the first conditional

- We find a digit at index 2 (zero-indexing, after all!)

- Ask: is that digit a zero and is everything after it a digit?

- This evaluates to

False→ the digit in question is a 5

- This evaluates to

- This is ok, because the zero is not the first digit. But the expression evaluated to

Falsein 3.1, so get the inverse of that with thenotkeyword since the function should returnTrueonly if the parameter passes

On the other hand, consider the case where the input string is CS05. We should expect this to be invalid, since the 0 is before the 5.

- There is a zero in the string, so skip the first conditional

- We find a digit at index 2 (zero-indexing, after all!)

- Ask: is that digit a zero and is everything after it a digit?

- In this case, this is

True→ it is a zero and there are digits after.

- In this case, this is

- Inverse the boolean to

False, since the function should returnTrueonly if the parameter passes

def no_punctuation(s):

return not any(punct in string.punctuation for punct in s)This is a fairly straightforward function, but it does make use of a very Pythonic feature called a list comprehension. This is essentially a for-loop used to generate a list. Another way of writing it would be:

punctuation_bools =[]

for punct in s:

if punct in string.punctuation:

punctuation_bools.append(True)

else:

punctuation_bools.append(False)In other words, if we evaluate punct in string.punctuation for punct in s we will get a list of bools. Suppose we enter the string “PI3.14” as an argument for no_punctuation, for example. Doing so will evaluate to: [False, False, False, True, False, False].

Now we can simply pass this list to any(), which will return True if any element of the list is True. Of course, in this case we want the elements to be False - we don’t want punctuation, and thus the negative not.

At this point, I believe, we have checked every individual requirement. However the final piece must still be assembled: all of these functions return boolean values, and for the program to call a license plate valid, all of them must return True. Which means we have to check each of them. The obvious thing would be to create nested if statements:

def is_valid(s):

if character_limits(s):

if are_numbers_at_end(s):

if valid_zeroes(s):

if no_punctuation(s):

return True

return FalseThat might work, but it is a bit unsightly - and what if we add more requirements? It seems a bit ridiculous to keep nesting the if conditionals. So what to do? Well, just like the counter-part of isdigit() is isalpha() we can use the counter-part of any(), known as all().

This function returns True if all elements in a list are True, and False for every other scenario. And fortunately for us, every function we wrote returns a boolean, which means we could simply write a list that evaluates each function, and thus gives us a list of boolean values. We can then pass that list to all and have all our checks done!

def is_valid(s):

return all([character_limits(s),

are_numbers_at_end(s),

valid_zeroes(s),

no_punctuation(s)

])nutrition.py

The final problem of week 2 is fairly straightforward: given a user’s input of a specific fruit, print how many calories that fruit contains according to the FDA. More than anything, I suspect this is a gentle introduction to the use of dictionary objects, or dicts.

In any case, the specific requirements are as follow:

- User must be able to input the name of a fruit

- Without regard for upper- or lower-case, print the calorie count of that fruit

- If the fruit is not on the list, or is misspelled, ignore the input.

The most time consuming part of this task was encoding the fruits and their caloric values into a dictionary:

RAW_FRUITS = {

"apple" : 130,

"avocado" : 50,

"banana" : 110,

"cantaloupe" : 50,

"grapefruit" : 60,

"grapes" : 90,

"honeydew melon" : 50,

...

}But it is perhaps also an example of a time when sure, I could have dug around, tried to find a text version, maybe curl the data or something and format it. Or, as I did, spend 5 min typing it in. At least for these many values (about 20 in total), this seemed reasonable enough.

With the RAW_FRUITS dictionary declared at the top of the file, the rest of the program is very simple:

def main():

fruit = input("Item: ").lower().strip()

if fruit in RAW_FRUITS:

print("Calories: ", RAW_FRUITS[fruit])

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()The input is converted to lower case so that case doesn’t matter, and I strip away any blank space either side of the string. Then using a simple conditional I check whether the given input matches any of the keys in the dictionary: if they do, print the value of that entry.